Benefitting from the Age of Efficient Corporate Management in Japan

May 15, 2020 Kevin N. Smith, Delft Partners

Kevin Smith takes a look at some of the long-term business management trends in Japan and the impact on reported profits and balance sheets. After two decades of reducing debt, corporate Japan is in a strong position versus their international competitors in a world of Covid-19.

In late 2019 we published two articles “Japan as a Safe Haven for Equity Investors” and “Two Steps Forward, One Back in Japan” which highlighted a number of positive aspects associated with the equity market as well as the potentially negative aspects of the proposed Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (FEFTA). The purpose of this article is to highlight the strength of corporate management in Japan, to reiterate our positive view of the equity market and to provide some comfort regarding the extent of any negatives associated with the FEFTA.

In the past decade, with the strong encouragement of Prime Minister Abe, corporate Japan has been transformed from a defensive inward-looking culture with a preference for market share over profits into a competitive open environment better aligned with the requirements of shareholders. The corporate governance code has been key to providing companies with a focus to improve return on equity which is now comparable with the best standards globally.

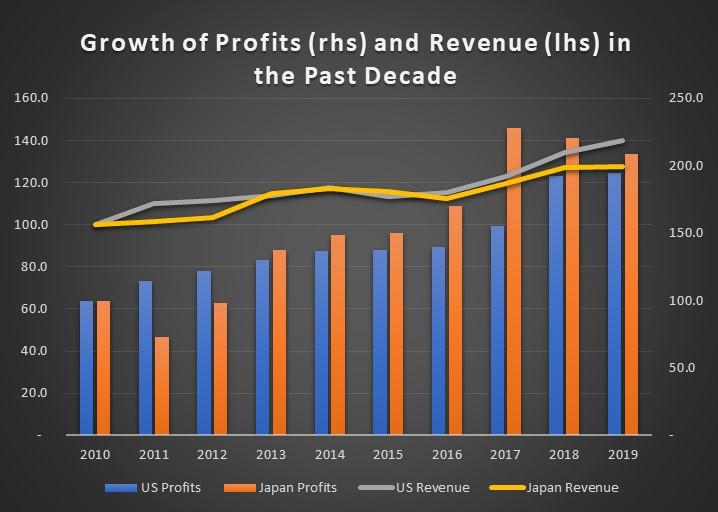

Table 1 shows a comparison of revenue and profits growth in Japan and the United States indicating that Japan is achieving results similar to the United States. During the past decade, the Japanese economy has remained sluggish versus the United States, with revenue growth of 2.8% and 3.9% respectively. Despite the weaker top line numbers, growth of corporate profits in Japan of 10.6% per annum comfortably exceeded the 7.9% per annum achieved in the United States.

Table 1

Source: Delft Partners/Refinitiv

That similarity in trends of revenues and profits between Japan and the United States was not translated into any convergence of equity market returns. In the past decade, the United States equity market has achieved a total return (net dividends reinvested) of 11.02% per annum which has significantly exceeded the 4.39% per annum return in Japan. In addition to stronger growth in profits, Japan has maintained an advantage over the United States with dividends to the extent of 0.4%-0.5% per annum, at the end of 2019 the respective yields in Japan and the United States averaged 2.2% and 1.8%.

In addition to corporate profits growth and dividend payments, the third crucial element of return is change in market valuation, typically measured by the price earnings ratio (PER). Ten years ago, Japan and the United States both stood on similar low teens valuations and in the subsequent period the PER in Japan contracted while the PER in the United States expanded. It was this PER expansion that has boosted returns in the United States to double digit percentage levels and the PER contraction in Japan that has offset the superior profit and dividend performance.

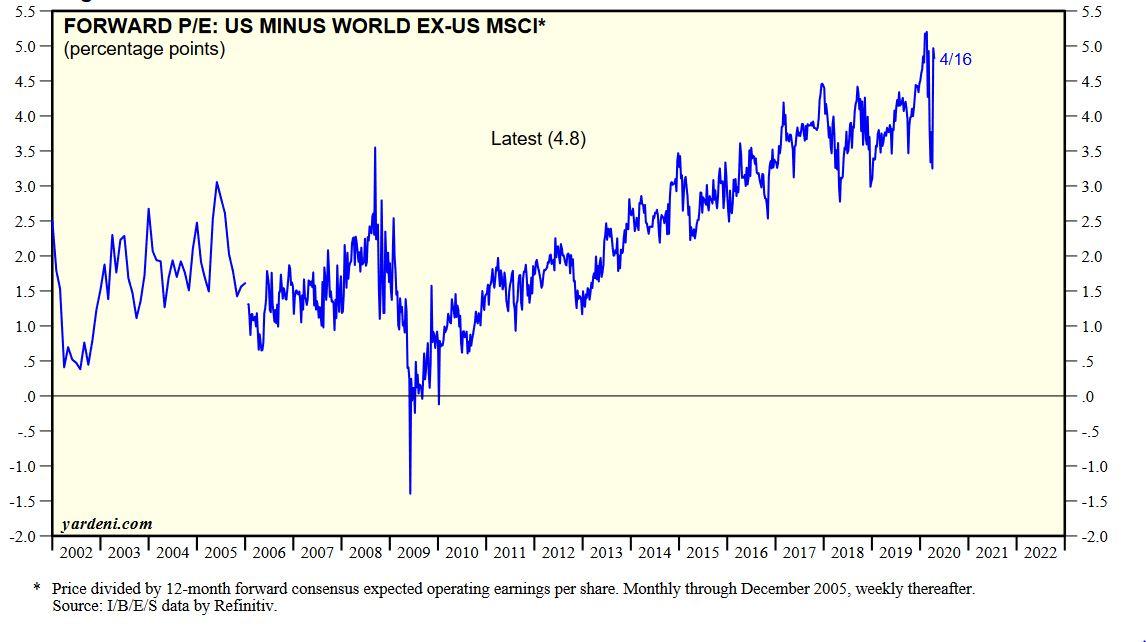

The extent of PER expansion enjoyed by the United States in the past decade is demonstrated in Table 2 which shows the PER premium versus the rest of the world. This expansion in the United States market valuation has been driven in large part (and justified) by the decline in interest rates. In an environment of corporate Japan continuing to match or beat profits achieved in the United States, the current level of valuation in Japan provides a wide margin of safety versus the United States.

Japan started the month of May 2020 on a forward PER of 14.2x versus the United States on 19.7x. Profits in 2020 will be subject to significant downgrades as a result of the economic lockdown measures put in place across the world in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. As economic activity returns to more normal levels in 2021, we expect the significant valuation difference between Japan and the United States become apparent once again and to begin to tilt returns in favour of Japan for the current decade.

Table 2

Source: Yardeni Research Inc.

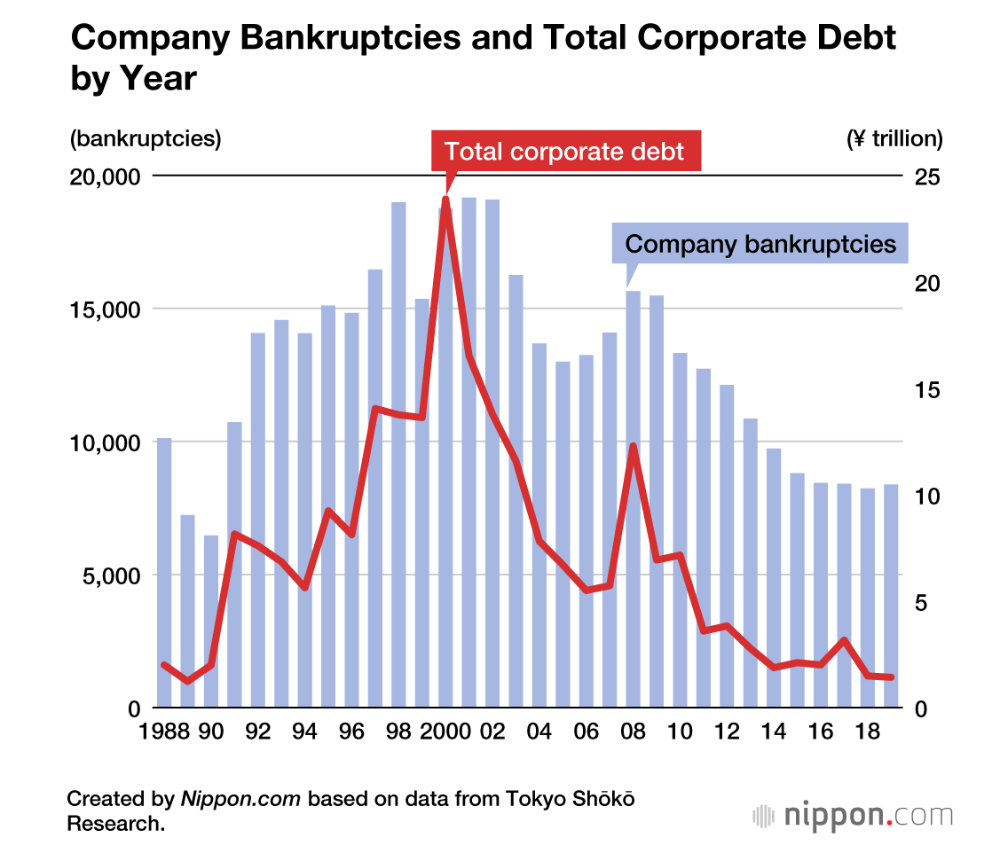

Companies with stretched balance sheets are vulnerable in the current economic environment, the extent of corporate debt is an area of stark contrast between Japan and the United States. Japanese companies have spent the past two decades improving their balance sheets and conserving cash. Corporate debt in Japan peaked in the year 2000 and has subsequently contracted by 94% as Japanese companies adopted a conservative strategy towards their balance sheets and businesses in general.

Table 3 shows the peak and subsequent decline of corporate debt in Japan courtesy of a recent article in Nippon.com1 which highlighted that the number of bankruptcies in 2019 hit the lowest level in 30 years.

Table 3

Companies in the United States have dramatically expanded the debt on their balance sheets in the past decade. In their recent article “Corporations Are Broke. It's Time to Cut Up Their Credit Cards”2 Christian Parenti and Dante Dallavale point out that following the corporate debt binge in the United States “the bill has come due”. In the United States since the 2008/9 recession household debt has declined while the average American company now carries debt to EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) of 3:1 an increase from a 2:1 ratio in 2009.

Twenty years ago, more than sixty American companies boasted triple A credit ratings, today there are two: Microsoft and Johnson & Johnson. This trend has seen half of all investment grade corporate debt rated triple B or lower with a third of those companies rated triple B minus, just one notch above junk status.

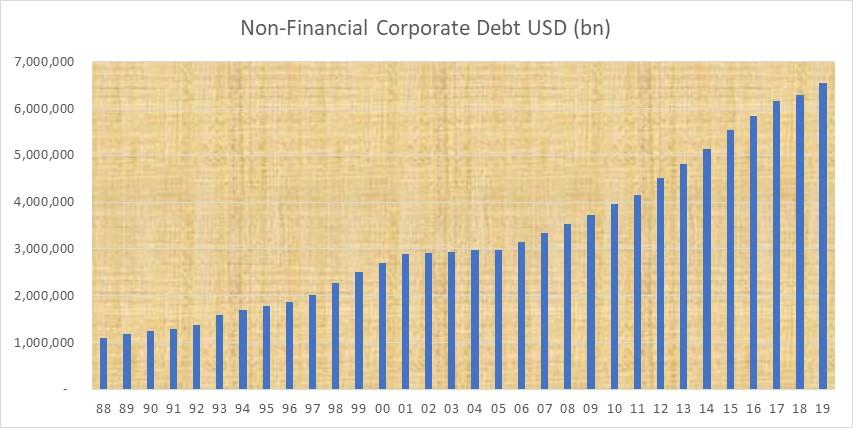

Table 4 shows the relentless rise in (non-financial) corporate debt in the United States since 1988 with the same time scale as Table 3. Globally the trend of corporate debt has followed a similar path as the United States, more than doubling in the past decade to USD 66 trillion. Japanese companies now have cash holdings equivalent to the current non-financial corporate debt in the United States. We will see rising bankruptcies in both the United States and Japan in the current year due to the extreme nature of the economic downturn.

Rating agency Moody has estimated that the default rate for “speculative grade” debt, that is companies rated at lower than triple B will increase from 2.3% in 2019 to more than 10% in the current year. The scale of bankruptcies or companies requiring bailouts is likely to be much higher in the United States than Japan. When we assess the quality of a company, we always prefer a strong balance sheet over a weak balance sheet and that provides another factor in favour of Japan.

Table 4

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

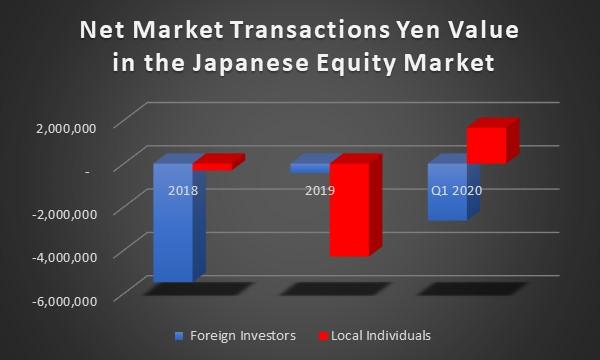

In our previous article we highlighted a trend of international buying in the Japanese market in the fourth quarter of 2019. The fourth quarter largely offset heavy selling of Japan by foreign investors in the first nine months of 2019. Domestic individual investors were net sellers in 2019. That trend has reversed in the early months of 2020, domestic individual investors have been net buyers while international investors have resumed their longer-term habit of selling. Domestic Japanese investors have also demonstrated confidence as net buyers of international equities in recent weeks. We believe that domestic investors as net buyers of the domestic (and international) equity markets are making better investment decisions than the international crowd.

International investors own 30% of the Japanese market and typically account for 60% of daily market volume. That degree of dominance over day-to-day trading activity has become an area of concern for the authorities in Japan, especially in periods of market volatility where the actions of international investors appear to be the cause of exaggerated market movements. We have previously highlighted the increased involvement of activist investors in the Japanese equity market. Those activist investors with a collaborative approach rather than a confrontational stance tend to achieve better outcomes in Japan.

Activist investors typically pressure companies to engage in share buy-backs and divestment of non-core assets, there is a time and a place for both activities. Japanese companies announcing a new buyback programme typically see a short-term share price reaction of plus ten to fifteen percent. Japanese companies tend to engage in buybacks for the right reasons, they have excess cash on the balance sheet and the buyback represents a productive use of the funds by boosting earnings per share.

Buybacks have been taken to an extreme in the United States, with four percent of the S&P 500 index capitalisation retired in the past year and companies engaging in the activity when their balance sheets are already stretched. For example, Boeing engaged in an aggressive buyback programme between 2013 and 2019 that resulted in 25% of the equity being retired. That strategy did not help generate long-term gains for shareholders when the company reported losses in 2019 and faces bigger losses in 2020 with a debt burden that more than doubled in consecutive years.

Table 5

Source: Refinitiv/IBES

The Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg did however enjoy a substantial boost to his wealth during the same period, especially in 2018 when his share options, based in part on earnings per share performance, helped boost his total compensation to USD 30 million for that year. Japanese CEOs tend to operate at a much lower scale of compensation that is much easier to demonstrate as being aligned with the interests of shareholders.

Average tenure of Japanese CEOs at seven years exceeds their United States counterparts by two years. That additional time in the role is helpful in directing the business towards longer term objectives. Good companies in Japan publish their medium to long term business plans with updates each year. When it comes to divestments, now that we have left behind the era of defensive cross shareholdings, Japanese companies are much better equipped to divest non-core assets and to focus on the delivery of strong returns for shareholders.

The authorities in Japan have become increasingly sensitive to issues surrounding ownership of technology especially since President Trump escalated trade tensions across the world. In mid-2019 Japan was very quick to accommodate President Trump’s demands for bilateral trade more favourably balanced towards the United States while at the same time taking a much tougher stance on the free movement of technology exports to South Korea.

The increased scale of foreign ownership of the Japanese equity market, trading volumes, the actions of activist investment and global trade tensions are all likely to have contributed to the proposed FEFTA legislation which has moved quickly from the consultation phase to implementation. On 8th May 2020, The Ministry of Finance published the list of 512 companies that are included in the FEFTA legislation which will require prior notification from international investors at the 1% threshold (reduced from 10%).

The Asian Corporate Governance Association published an open letter to the Ministry of Finance on 9th April, highlighting that the new rules represent “a step backwards for corporate governance in Japan”. There is little doubt that the 512 companies named by the Ministry of Finance will become less attractive targets for activist investors in the near-term, however, we expect a gradual relaxation of these rules in the next few years. International investors with a long-term time horizon have nothing to fear from these new rules, however, activists attempting to engineer hit and run strategies will be hindered by the FEFTA rules. We remain confident that the trend towards better governance and management alignment with shareholder goals is firmly in place.

In conclusion, the past decade has seen dramatic improvements in the management of Japanese companies, with profitability outcomes as good or better than those achieved in the United States. Those profitability improvements in Japan have been achieved against a backdrop of dramatic reductions in the levels of corporate debt which is in marked contrast to the United States where debt levels have doubled in the past decade, and now stand at extreme levels.

The strength of balance sheets are a critical factor in the ability of companies to survive in the Covid-19 economic environment of 2020 and 2021. During the next decade we expect the strength of corporate Japan to be recognised with expanding valuations in a reversal of the experience of the previous decade that resulted in 10% annual profits growth converted into much lower returns for investors. The FEFTA legislation is a minor setback in a positive long-term trend for investors, both foreign and domestic, in corporate Japan.

2https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/corporate-debt-crisis-coronavirus-financial-covid-19

DISCLAIMER

This report provides general information only and does not take into account the investment objectives, financial circumstances or needs of any person. To the maximum extent permitted by law, Delft Partners Pty Ltd, its directors and employees accept no liability for any loss or damage incurred as a result of any action taken or not taken on the basis of the information contained in the report or any omissions or errors within it. It is advisable that you obtain professional independent financial, legal and taxation advice before making any financial investment decision. Delft Partners Pty Ltd does not guarantee the repayment of capital, the payment of income, or the performance of its investments. Delft Partners operates as owner of API Capital Advisory Pty Ltd AFSL 329133.