Some stuff you don’t want to think about – but should.

Or Risk is the independent variable and Return, the dependent one.

Ever been on a car journey as a passenger where the driver was going too fast; being reckless; and essentially taking chances? Over and under-taking, switching lanes without looking, going too fast and braking too hard. We all have. It’s not so pleasant especially as you get older and realise how much is at risk from a needless mistake: your health, your life even; the realisation that family members depend on you staying healthy and not becoming a burden; your enjoyment from their growing old.

So, we try to avoid such a scenario. It’s relatively easy since reckless driving is usually associated with inexperienced younger members of society in fast cars. So, we can avoid such journeys as being readily identifiable in advance.

And yet we often find that a similar journey, multi-generational wealth investing, has older wealthy members indifferent to risk and unaware of the loss of wealth that occurs when insufficient attention is paid to the risk path taken by their managers.

Investing is not so different from a car journey? It’s a path to an end point with risk to be managed; speed, comfort, time horizon all matter for investing as much as they do for being driven. Better to get to the end point safely and aware of risks on the way, and how to drive defensively at such times, than to get there at speed dangerously?

And yet here we are, perhaps caused by years of unorthodox monetary policy, where many managers and clients perceive risk as irrelevant and an irritant? All focus is upon return – those ‘sexy’ growth stocks, that 10 bagger PE fund, that property that will inevitably benefit from a lick of paint or a change of use permission, and of course the free put option available to all investors that has been a feature of monetary policy in essentially the last 25 years.

So we're going to bore you with a brief article on the independent variable known as risk. Return, the glamourous bit, is the dependent variable. No risk, no return. So, if you can’t define, measure, and manage risk then your returns are a function of luck. Not a lot of people know that.

We spend a lot of time obsessing about risk especially in multi-asset portfolios, whose Alphas and Betas are both correlated at different extents at different times, and where they offer differing opportunities for active and passive approaches at different times.

The cost of variance or variance drain

The variance of returns over time directly impacts our ability to grow wealth. $100 invested at 5% interest for 30 years grows to become $432. Of that, $100 is of course your initial capital, $150 is the total amount of simple interest paid, and $182 is the effect of compounding – interest on interest. (Let’s assume away the taxman?!)

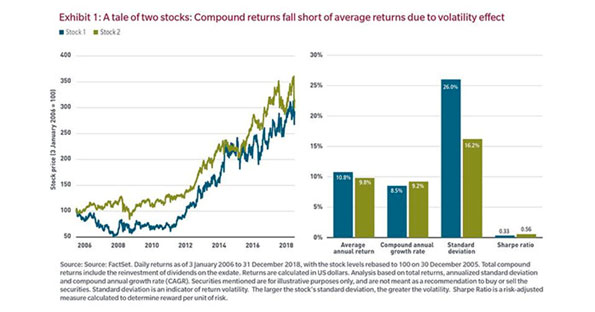

Once uncertainty in returns (volatility) is introduced into the mathematics, there is an immediate noticeable drain. If that same investment still yields 5% but now with a volatility of 17% (like a typical equity index ) the cumulative growth rate – the rate your wealth actually grows over time including rises and falls – is now just 3.56%. After 30 years you will have instead of $432 just $285, and you will have lost almost $150 to volatility. Risk is expensive!1 A lower-return investment with a lower risk may often outperform a high-return high-risk alternative.

Multi-asset portfolios of course mitigate the high volatility from equity and many investors choose hard assets to go into the mix since their price is ‘not volatile’. However, bonds, especially high yield bonds, can behave like equities at certain times 2 and an absence of price volatility shouldn’t be equated with an absence of risk 3. For example, if you own a physical property whose revenues are derived from retail tenants, and your equity portfolio is heavily weighted to retail and consumer companies, guess what happens when a general consumer recession hits. That ‘lack’ of volatility in the property will suddenly not be so lacking as your cash flows from rental payments dry up and the next valuation of the property will be a jump down in value, and a reduction in re-investable cash flows, just when you most needed to be immune from volatility as a drain on wealth.

The infrequent tails that happen too frequently

We tend to think of “drawdowns”, crashes, corrections, shocks or other sudden unusual “non-Normal” events as a completely different animal from typical market volatility. When we consider investments, we should consider not just volatility or tracking error but also the incidence of these drawdowns. Simple mathematics to transform mean and volatility without drawdowns to equivalent numbers that correctly include the effect of such infrequent drawdowns has been known for almost 100 years 4. If we make this adjustment to historical return series, we observe two troubling effects. First, the historical “alpha” that is often reported in academic papers and relied on by active managers from factors like Momentum, Size, Value, or Beta, once adjustments for drawdowns have been made, either radically shrinks, or disappears, or reverses sign and becomes a persistent drag. This phenomenon is described at length in one of Northfield’s recently published journal articles 5. Secondly, adjusted volatility numbers are usually much bigger than the unadjusted numbers – meaning that these investments have both a lower return and a higher risk than would at first appear. The effect of that higher risk is once again, as above, to reduce the effectiveness of compounding. Investments that experience periodic shocks have both lower return than would appear at first glance, and higher risk. Drawdowns are also expensive!

The evasive Alpha

Another closely related aspect is uncertainty in active management. Unfortunately, Alpha is hard to find, easy to lose, and always changing.

Because Alpha is uncertain, we should include that uncertainty in our calculations of risk – in this case it is “the risk of being wrong” or strategy risk 6. It may come as some surprise that usual risk measures completely ignore this and assume that the managers’ return is known with certainty. We wish it was. With active management we deliberately move away from the benchmark return and believe that we have a new mean return (our alpha) that is bigger than the benchmark. Tracking error, which originated in passive management, or value at risk, or any other measure that is based on volatility measures variability or uncertainty around the mean (alpha) and says nothing about variability or uncertainty of the mean (alpha) itself. As with all the previous examples – you might be spotting a pattern here – correct inclusion of strategy risk makes the total actual risk of the investment larger, which once again negatively impacts compounding. Active management where big bets are taken is risky and being wrong is very expensive indeed!

There is no such thing as linear in the world of risk

There is one additional implication of compounding that is utterly ignored – if we consider the compound return, as we should, given its importance to us, then return no longer increases linearly with risk as we are told by the textbooks 7. It is now a convex function, and as risk increases past the peak, our return begins to decline with increasing risk.

This has serious implications for asset allocation. In every market there will be a “peak beta”, beyond which as explained returns decline with increasing risk, so we must stay to the left of that peak. This tends naturally to send us looking for lower beta stocks, or into multi-asset class portfolios 8.

So, what to do?

Experienced judgement helps. By experienced we mean professionals whose careers extend back to when corporate failure was possible, when central banks tightened monetary policy as much as they engaged in QE and granted a free put option, and when dividends and balance sheets mattered.

Models also help to provide a framework for identifying, measuring, and managing the Betas and the Alphas and their correlations and payoffs. Many fund managers do not use risk models and are ignorant of the absence of diversification of the risk sources in their portfolios. Many don’t want to know and prefer a ‘pedal to the metal’ approach.

We acknowledge that all models are ‘wrong’ but believe that some are useful. The useful ones such as the Northfield model we use ( www.northinfo.com ) allow liquid and illiquid asset forecasts to be combined; have data on bonds as well as equities, allow scenario and stress testing, and incorporate the multi-generational time horizon and planning for periods of investment and consumption that many plan sponsors will have to manage.

We conclude that successful wealth management requires carefully nurtured compounding. This compounding can only occur when three forms of risk are carefully managed the exposure to volatility from risk factors and asset-specific sources, the risk of drawdowns, and strategy risk – the risk of being wrong.

Portfolios are constructed by focusing risk exposures only in areas the manager has skill.

- 1 E.g. www.morningstar.com/indexes/xasx/xko/risk

- 2 It’s not hard to understand why – equity and bonds are issued by the same underlying entity. If the entity is relatively well financed and stable interest rate risks will dominate, however if the entity’s future is less certain then credit risk concerns will dominate. Obviously the same factors that drive equity risk also drive credit risk – it is the same underlying business of course. See Merton’s paper https://www.jstor.org/stable/2978814

- 3 Northfield’s award-winning real estate model looks beyond appraisals to avoid this problem. https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/files/resources/essays-monographs/2014-erm-symposium/mono-2014-erm-belev.pdf

- 4 See for example “Moments and Cumulants in the Specification of Distributions”, by E. A. Cornish and R.A. Fisher (1937), or Edgeworth expansions: http://personal.psu.edu/drh20/asymp/fall2004/lectures/edgeworth.pdf

- or Maillard, Didier, A User’s Guide to the Cornish Fisher Expansion (May 1, 2018). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1997178 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1997178

- 5 Kantos, DiBartolomeo “How the pandemic taught us to turn smart beta into real alpha” Journal of Asset Management (2020) 21:581–590 https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-020-00195-w

- 6 See: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=569281

- 7https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/sml.asp

- 8https://www.northinfo.com/documents/576.pdf

DISCLAIMER

This report provides general information only and does not take into account the investment objectives, financial circumstances or needs of any person. To the maximum extent permitted by law, Delft Partners Pty Ltd, its directors and employees accept no liability for any loss or damage incurred as a result of any action taken or not taken on the basis of the information contained in the report or any omissions or errors within it. It is advisable that you obtain professional independent financial, legal and taxation advice before making any financial investment decision. Delft Partners Pty Ltd does not guarantee the repayment of capital, the payment of income, or the performance of its investments. Delft Partners operates as owner of API Capital Advisory Pty Ltd AFSL 329133.